All about ceramic glazes

The Créamik school has specialized, among other things, in teaching the making and the application of glazes – thanks to the in-depth work of Matthieu Liévois for more than 45 years. But for those who are starting on this journey the world of glaze can be mysterious.

You will find in this article the basics for understanding what a glaze is, what it is used for, its composition and how to apply it. Acquiring a first overall vision of ceramic glazes is important, you can later go deeper into all its details: why not embark on the adventure!

There is no such thing as a stupid question! Do not hesitate to read this article attentively, and then ask anything in the comment section. And if some of the content is still a little unclear to you, we will be there to help.

Summary:

What is a ceramic glaze made of?

Why is the mixing of powdered ingredients essential?

How to differentiate between colouring oxides and other oxides

The secrets of creating a glaze recipe

What is a ceramic glaze?

A glaze is a melted glass that covers a ceramic piece and protects it. It is made by mixing powders of crushed rocks, such as silica (the main ingredient), kaolin and feldspar.

Once applied to ceramics, a glaze must be fired at very high temperatures to make it melt and become glass: a potters’ kiln can go up to 1300°C.

What is a glaze used for?

Glaze has two main functions: to protect a ceramic piece and to decorate it.

Protecting a ceramic piece.

Protecting the pottery from shocks and wear is the main role of a glaze. Since it is a molten glass, the glaze is much more resistant to wear than the unglazed pot. Even if, like glass, a glazed pot will break under a strong impact, it will crumble less easily than an unglazed pot. Once glazed, the ceramic piece will therefore be more resistant to small shocks and will be less likely to chip.

Glaze is also used to:

- Optimise functional ceramics for food use. When glazed, pottery intended for tableware has a smoother surface than unglazed pottery. It is therefore easier to wash. You can read more about food safe glazes in our article on this topic.

- Permeability of earthenware. When earthenware clays are bisque fired to a temperature between 998°C and 1060°C, they remain porous after firing. In other words, air and water can still pass through. Water poured into an earthenware container will seep out if it is not protected with a glaze.

Decorating ceramics.

Glaze is also used to decorate ceramics, to give them colour and a particular final surface texture.

Texture

A glaze alters the surface texture of pottery. Without it, the pot will be rougher to the touch. A glaze makes it possible to create different sensations: from the totally smooth feeling of a perfectly melted and shiny glaze to a rough, stony finish, or a satin, velvety or even matte effect.

It’s hard to represent these sensations in photos… but experience it! If you don’t have any ceramics at home, imagine touching the smooth inside of an oyster shell, then the rough outside. The texture changes the visual, but also the tactile experience.

Imagine holding a cup of hot coffee in your hands: the texture of the cup is an essential part of the pleasure and must absolutely be considered by the ceramicist when creating his or her line of products. In this sense, glaze plays a very important role in the creation of a ceramic object.

The texture of a ceramic piece will also influence how the colour appears. The glossier the glaze, the more vivid the colour will be.

Colour

Colour is an essential part of a ceramic object.

If you use a low temperature earthenware glaze, you will be able to create patterns with clear outlines and, in effect, draw on the clay surface.

If you use a high temperature glaze to create your colours, you will not be able to decorate the piece so precisely. These glazes tend to run or “move” on the surface during firing. But they bring beautiful effects, which would be impossible to achieve drawing by hand.

Choosing which type of glaze to use is therefore an artistic choice.

There are other ways to bring colour to a ceramic object. An engobe (or slip), for example, is clay mixed with water, which is applied in a similar way to a glaze, to add colour and variation (if a colouring oxide is added). However, a slip is not a glaze because it will not vitrify. As it does not melt, it will be easier to make precise drawings, but its colours will be less vivid.

It is possible to use a slip to create a design, then cover the whole thing with a transparent glaze to provide protection and impermeability. We explain how to make engobes in our article.

What is the composition of a ceramic glaze?

Any glaze recipe consists of a mixture:

- mostly silica

- a small quantity of alumina (on average one tenth of the amount of silica)

- an assortment of basic pH ingredients, called fluxes, such as potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, etc.

- colouring oxides, in very small quantities, to create colour.

Silica, the main ingredient

Silica is the main ingredient in a glaze recipe since it generally constitutes about 80% of the mixture. Silica is what gives a glaze its hardness. There could be no glaze without silica. Silica is, so to speak, the “skeleton” of the glaze.

Even if silica doesn’t mean anything to you, you have already encountered it in nature: the sand on our beaches is quite simply grains of silica! Silica can also be found in the form of compact rocks, such as flint. Silica is also found combined with other components to create hard rocks, such as granite.

It is also silica that we melt to create the glass in our windows, or our mirrors. This is why we can say that a glaze is a glass, just like the glass in our windows.

Why silica must be mixed with other ingredients

Silica cannot be used alone in the manufacture of a glaze. It has a natural melting point of 1710°C (3110°F). Below this temperature, silica (or grains of sand or flint), ground to a powder will not melt, and therefore not turn into a protective layer for ceramics. It would be impossible to melt it in a potter’s kiln (which can only reach a maximum of 1300°C (2372°F)).

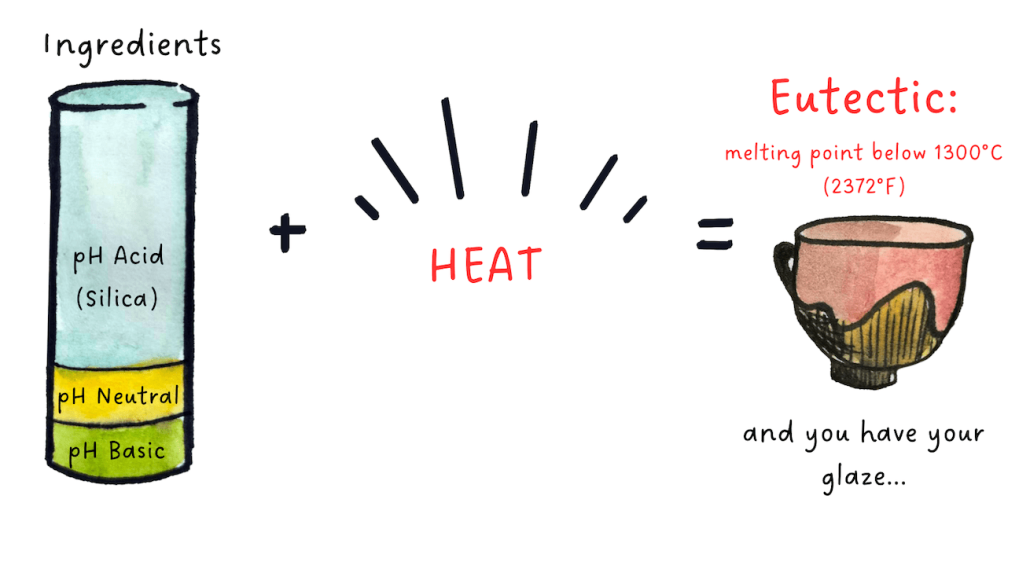

Fortunately, there is a surprising natural phenomenon that solves this problem: when ingredients belonging to three different pH categories are brought into contact at high temperatures, their respective melting points drop! This natural phenomenon is called “eutectic” and forms the basis of the techniques for creating glazes. Without this phenomenon, it would be impossible for ceramicists to create glazes.

For the eutectic to work, all three pH categories must be present: acidic, neutral and basic. Controlling the proportion of these three types of ingredients therefore makes it possible to control the temperature at which a mixture will melt.

Thus, in addition to silica, which is acidic, the second absolutely essential ingredient in a glaze is alumina, which is neutral.

The association between silica and alumina is what will most influence the lowering of the melting point of the glaze, and as such, it is essentially the proportion between these two elements that will influence the glaze texture. The more perfectly melted a glaze is, the shinier it is. The less it is melted, the more it will have a matte, even stony appearance. Depending on the desired texture, the ceramicist varies the proportions of these two elements. As a result, alumina is also considered part of the “skeleton” of the glaze.

Finally, for the eutectic to work, with silica and alumina, the fundamental ingredients for obtaining a glaze that vitrifies, basic elements must be added. There are about ten frequently used basic pH ingredients (sodium, potassium, calcium, lithium, magnesium, etc.).

Colour provided by metallic oxides

A glaze consisting solely of the elements mentioned above (silica, alumina, basic oxides) will only give gradations of transparency in a neutral glaze, i.e., without colours. We often call a transparent glaze “a cover” because its role is limited to providing a protection to the ceramic piece.

To colour the glaze, metal oxides, also called colouring oxides, are added in very small quantities: they often constitute less than 2% of the recipe. They give ” the spark of colour ” which the rest of the body of the glaze will amplify.

Metal oxides can have an acidic, neutral or basic pH. But their presence will only very rarely influence the eutectic, because they are present in too small a quantity.

Note that the basic pH ingredients play a very big role in the final rendering of the colour of the glaze. By choosing and experimenting with all these ingredients and their proportions, the ceramicist learns to develop his creativity.

For this, it is useful to know the qualities and drawbacks of each ingredient. For example, sodium promotes the shiny side of a glaze, and creates very beautiful Egyptian blues, when used with the right colouring oxide. Lithium also develops particularly shiny glazes, and does not cause crackling (unlike sodium).

In our online course on glazes, we go into detail about the pros and cons of all the main ingredients used to make glaze, whether simple oxides or colouring oxides.

How colouring oxides can be differentiated from other oxides

All the raw ingredients used to make glaze are in the form of oxides: silica (silicon dioxide), alumina (aluminium oxide), basic oxides, and metal oxides. An oxide is an element that has oxidized, i.e., that contains oxygen.

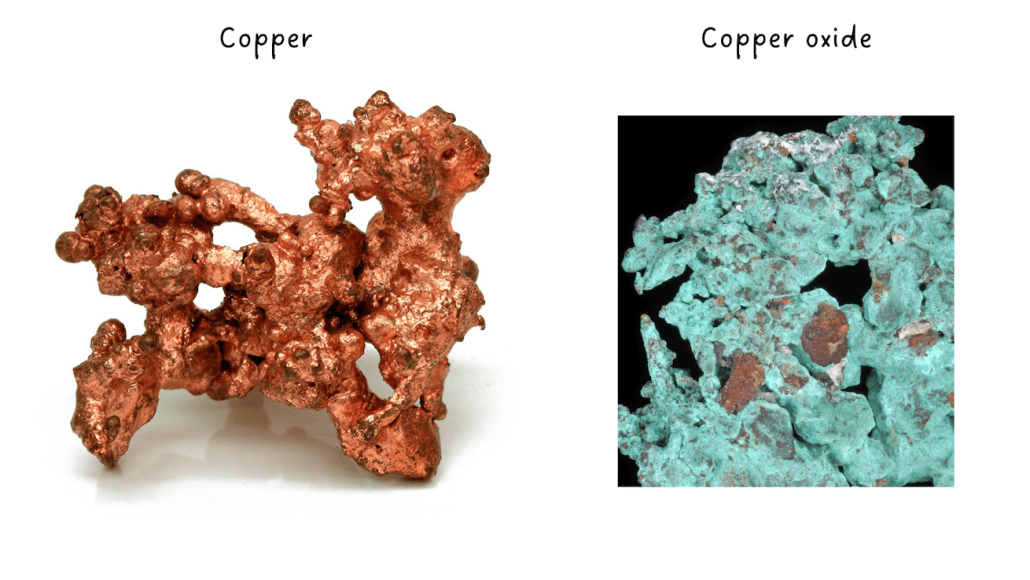

Thus, there is a difference between copper, a metal, and copper oxide, a metal oxide derived from copper.

But in the world of ceramics, we use the word ” oxides ” to talk mostly about ” colouring oxides ” (or metal oxides). This can be a confusing way to use the word “oxide”: all ingredients needed to make a glaze are actually oxides. So, be prepared for some confusion: when you talk to a ceramicist about “oxides”, be sure that you understand which oxides she or he is talking about!

In practice, the oxides that form the body of a glaze are differentiated from the colouring oxides by their appearance in a powdered state.

Any non-colouring oxide, when ground into powder, turns white (or a colour very close to white). Exactly like ice which, when crushed, turns white (it’s snow!). But a colouring oxide, when ground, retains a coloured tint.

The secrets of creating a glaze recipe

Some ingredients used in a glaze cannot be added to a recipe in a pure form. This is the case for example of alumina, which is added in the form of kaolin, a clay composed of silica and alumina.

Why use kaolin rather than pure alumina? Because the latter mixes very poorly with the rest of the ingredients when water is added. The alumina settles at the bottom of the container. Result: The liquid glaze is not homogeneous. But only a homogeneous glaze causes a good eutectic.

Kaolin, on the contrary, is very useful: in addition to mixing well, it will allow all of the glaze powder to remain in suspension in the water and thus better results will be obtained when applying glaze on ceramics.

Other ingredients, such as sodium and potassium, simply do not exist on their own in a state that can be used for glaze (on their own, they dissolve in water, like salt). They must therefore be accessed in the form of a powdered rock, feldspar, which also contains silica and alumina.

Mixing ingredients in very precise proportions, when you can only use products containing several ingredients such as feldspar, can quickly become a headache. But fortunately, generations of ceramicists before you have looked into this and found a system that you can easily use to find the exact proportions of material you need to create a recipe.

These days, there’s even software online, like the fantastic Glazy, that does almost all the work for you. But the fact remains that it is still important to understand the logic of the whole process to create a recipe. This is what we explain in detail in our online course.

How to apply glaze

If learning to make a recipe for a glaze is essential, the way in which this glaze is applied plays a very big role in the final rendering of your ceramic piece. Choosing how to apply a glaze is therefore part of the artistic process of creating excellent work.

Glaze application techniques

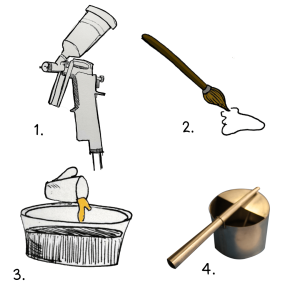

Glaze can be applied using:

- a spray gun in a spraying booth

- brushstrokes

- by dipping the pot, or pouring the glaze onto it

- Glaze atomizing spray gun

We describe the pros and cons of each method in our online course. The financial side of it must be considered because certain application methods, such as spraying with a spray gun for example, require a bigger investment (the lowest price of a spraying booth is €1500, and they can go up to €5000 depending on efficiency and size).

Combining or superimposing different glazes on the same piece allows even more creativity. Layering is a technique that Matthieu has made a specialty, we are devoting a whole article to it, which you can find here.

The importance of firing

Not all glazes melt at the same temperature: the melting point will depend on the proportion of ingredients in the powder mixture. Some glazes can melt from 980°C (1796°F), others at 1060°C (1940°F), 1245°C (2273°F), or even 1300°C (2372°F). They each have their own characteristics and as we have seen, they do not give the same colour.

In short, there can be a world of difference between the glaze before firing and when you open your kiln! Glazes in their raw state often have a neutral, whitish, pinkish colour at best, which does not at all represent the final colour after melting in the kiln.

This brings another difficulty for the ceramicist, who must mentally visualize the result of their pot when applying the glaze, hoping that the final rendering will correspond to his or her expectations. If this can cause a little stress at the time of creation, it also offers a moment of pure magic when it comes out of the kiln: when the ceramicist discovers for the first time how their glaze has turned out!

Moreover, colour is not only decided once you are ready to put your ceramics in the kiln; the way in which the firing is carried out can radically change the results.

The type of firing can cause unique effects, such as the metallization or the crystallization of a glaze (the creation of “glaze flakes”).

If the firing is carried out in an oxidizing atmosphere (with a lot of oxygen in the kiln) or in a reducing atmosphere (with much less oxygen in the kiln), certain colouring oxides can give radically opposite results.

Copper oxide, for example, can result in a green colour in oxidation, and red in reduction!

If you liked this introduction to the world of glaze, and you want to find out more, don’t hesitate to subscribe to our newsletter (at the bottom of the page),to receive immediately in your inbox, a link to a free 30-minutesample video from our online course!You will also be able to discover part of the explanations of this article on video in our short 7-minute video: what is a glaze?.

Resource centre

animated by Matthieu Liévois,

potter-ceramist for over 40 years and founder of the Creamik School

Find all the courses

Keywords

Don’t miss any more news from the Créamik school!