Tea and ceramics, a thousand-year-old story

Contents

1 – The history of ceramics associated with tea

3 – Materials, techniques, design and aesthetics

4 – Current trends in the world of tea

Introduction

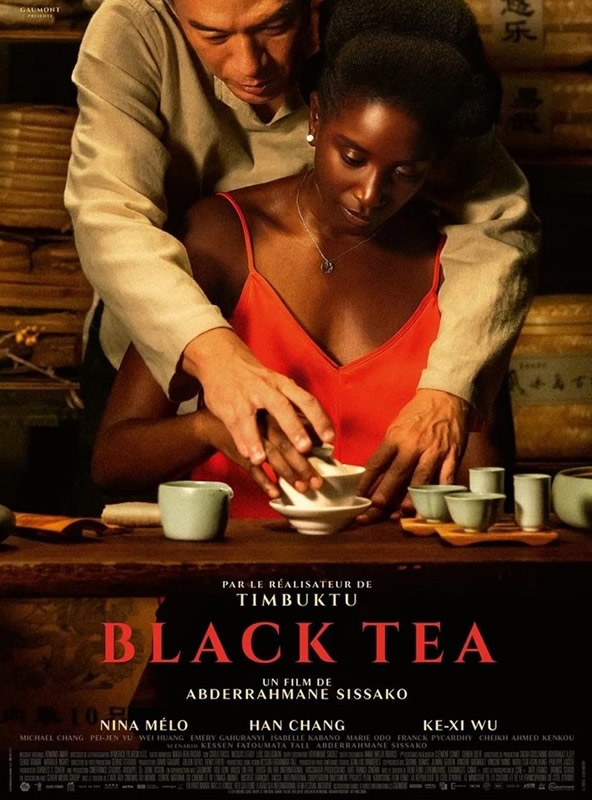

Tea and ceramics, both thousands of years old, share a beautiful and enduring history, and continue to inspire many potters. Films and television shows confirm the abiding public interest in tea. The film “Black Tea” by Abderrahmane Sissako (director of Timbuktu), due for release on 28 February 2024, promises an immersion in the world of tea. At the same time, “The Great Pottery Throw Down”, (broadcast on Channel 4 in the UK, 11 February 2024) highlights techniques used in making objects associated with tea, challenging its participants to create a teapot.

Just watching the Black Tea trailer tempts us to delve deeper into the world of tea, while the Great Pottery Throw Down challenge highlights the art and technique of making a teapot. These cultural events highlight the importance of tea and ceramics in their artistic dimension, and as vectors of enriching human experience.

Over the centuries this delicate infusion, has become part of many cultures around the world. Tasting it has become an art – one where every detail counts. Ceramics are inseperable from tea drinking, because it is within hand-made clay vessels that the tea’s flavours are experienced.

This article explores the symbiosis between tea and ceramics, a relationship that extends far beyond functionality.

The history of ceramics and tea

Ceramics have been used to prepare and enjoy tea since tea-drinking began to flourish in Asian countries.

Origins of the use of ceramics for tea:

Tea-related ceramics originated in China, where tea was first cultivated and consumed. Chinese ceramics dedicated to the preparation and tasting of tea appeared around the 3rd century AD. These objects were simple and functional, reflecting the Taoist philosophy of simplicity and harmony with nature. The first Yixing terracotta teapots, renowned for their ability to absorb the aromas of tea, are typical of this early period.

Evolution of different cultures:

China

In China, changes in the preparation of tea (using bricks of compressed tea, loose leaves, powders, etc) led to new ceramic forms. During the Song dynasty (960-1279), the popularity of powdered tea gave rise to bowls famous for glaze that imitated jade. It was not until the following dynasty, the Yuan dynasty, that teapots were introduced. With the advent of loose-leaf tea during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), teapots became smaller, allowing for a more concentrated and personalised infusion.

Japan

Tea and ceramics were introduced to Japan by Buddhist monks in the 9th century. Inspired by the Chinese practice of whisking tea powder, the Japanese tea ceremony, or ‘chanoyu’, had a major influence on the design of ceramics. Matcha bowls, known as ‘chawan’, have become emblematic of this tradition. They are often rustic, evoking the Wabi-Sabi philosophy: finding beauty in imperfection and simplicity The raku, hagi and karatsu styles are some of the most famous examples from this period.

Europe

Tea was first introduced to Europe in the 16th century by the Portuguese via the Macao trading post. But it was not until the 17th century that the tea trade really took off. It led to a revolution in Western ceramics. Initially, tea was drunk from cups imported from Asia or from silver vessels. However, European porcelain quickly gained in popularity. Manufacturers such as Meissen in Germany, Sèvres in France and Wedgwood in England began to produce highly elaborate teapots, cups and saucers. Often adorned with sophisticated designs and bright colours, this delicate tableware reflected the tastes and trends of the European aristocracy.

The tea ceremony

CheChe — CC0

The traditional tea ceremony has its origins in China. It is a refined practice of tasting tea after meticulous preparation using specialised utensils. Deeply rooted in Taoist philosophy, it emphasises harmony with nature and the quest for balance. Gongfu Cha, the Chinese tea ceremony, creates a moment of tranquillity that highlights the aesthetic and sensory pleasure of tea.

Imported from China by monks, the tea ceremony took on a distinct form in Japan, influenced by Zen Buddhism. This practice, known as ‘chanoyu’, transcends the simple drinking of tea to become a spiritual practice. Zen principles such as meditation, mindfulness and the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic are integrated into the ritual, with the aim of transforming every gesture into spiritual contemplation.

The Japanese tea pavilion, or ‘chashitsu’, and the attention paid to the details of tea preparation and presentation illustrate a quest for harmony, respect, purity and tranquillity. These values, embodied by masters such as Sen no Rikyu (16th century), resonate deeply with Japanese culture, making the tea ceremony a representation of aesthetics and philosophy of life.

To find out more: read the article ‘The secret of the mystical calm of Raku tea bowls.’

A superb matcha bowl in the Chōsen Karatsu-yaki (朝鮮唐津) style, entirely handmade by master Kimura, in which a layer of white glaze and a layer of black glaze merge, symbolising the unity of opposites well known in Zen philosophy.

The tea ceremonies in China and Japan reflect the nuances of their respective cultures and philosophies. In China, the experience is centred on tasting, valuing the diversity of flavours and methods of preparation in a variety of environments. In Japan, chanoyu is a profound expression of a spiritual path, where each element of the ritual is charged with meaning, with a view to achieving inner harmony and a contemplative state.

The tea ceremony is also present in other Asian countries, each with its own traditions and meanings. In Korea, the tea ceremony, known as ‘Darye’ emphasises the simplicity and natural flavours of tea. Although there are very ancient traces of tea being offered to deities, the Korean tea tradition developed particularly during the Joseon period (1392-1910). In Vietnam, tea culture, strongly influenced by its neighbours, is a relaxed, social activity. The Vietnamese tea tradition, although less formalised as a ceremony, has been an integral part of daily life for centuries. These differences between tea ceremonies show how a practice can be adapted and transformed by different cultures, each bringing its own interpretation and values, enriching the tradition.

Although the “way of tea” (‘chado’ or ‘sado’) has lost some of its spiritual depth, the tea ceremony is still practiced today, both in the original Asian countries and around the world. It is still taught as an art form and integrated into daily life in Japan, China and Korea. The growing interest in meditation and mindfulness has contributed to a renaissance of the tea ceremony in many other countries, where it is embraced as a spiritual and relaxing practice.

Materials, techniques and aesthetics

Let’s delve into the technical world of making teacups and teapots. Which materials were first used?

Stoneware and porcelain

Stoneware was used before porcelain was developed. Stoneware, known since ancient times, was widely employed for its robustness and ability to retain liquids. Its dense, non-porous texture ensures excellent heat retention and maintains the flavour of the tea.

Porcelain, because of its fineness and translucency, can be used to make lighter pieces, while retaining their heat-retaining qualities. Porcelain was developed in China during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), where its use flourished and it became the material of choice for tableware. Other civilisations gradually adopted porcelain for its aesthetic qualities and superior strength.

Cups and bowls

Teacups vary greatly according to cultural traditions. In the West we use teacups, fitted with a handle to avoid burnt fingers. But in many Asian cultures, tea bowls have no handle at all. The drinker is encouraged to place his or her hands directly around the bowl, enjoying the warmth of the tea.

Teapots

Potters love making teapots, despite the complexity of the work. First and foremost, making a teapot is an artistic and technical challenge that allows potters to showcase their skill and creativity. Each part of the teapot – the body, lid, spout and handle – must be crafted separately, and then assembled as a harmonious unit. The spout alone is a challenge.

Although time-consuming and therefore less profitable than other forms, the teapot can be seen as the emblem of a long craft tradition. When making a teapot, potters perpetuate a cultural heritage, while adding their own personal touch.

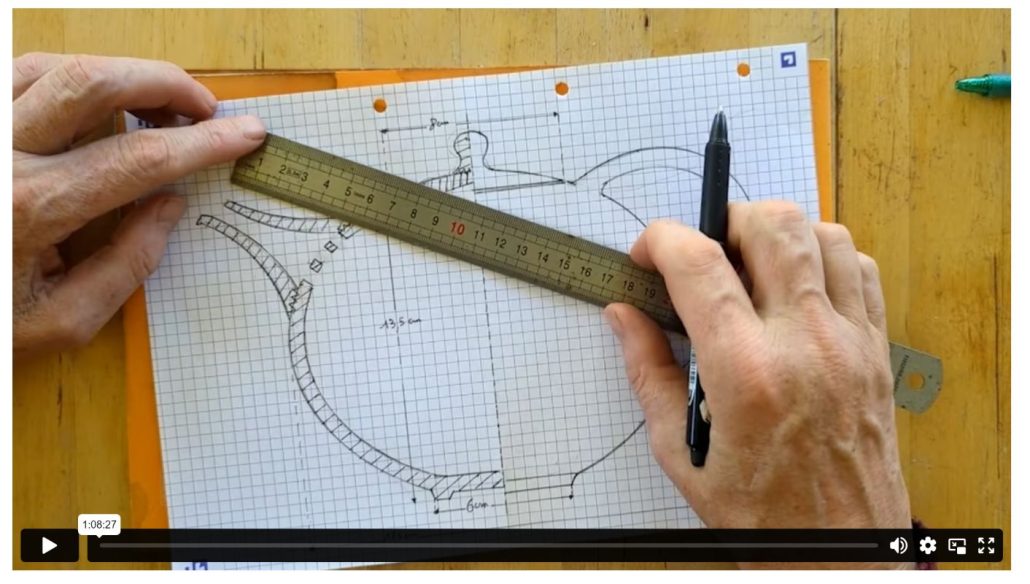

With the “Créamik Creativity Subscription online” technical drawing course, (currently available on the French site) you can learn how to create design diagrams of ceramic forms. Let’s take the example of the round teapot that we learned to throw in the intermediate throwing course:

Some famous designs :

Yixing teapots

Yixing teapots, from the Yixing region of China, are renowned for using a special clay known as ‘zisha’ (purple clay). It gradually absorbs the aromas of the tea, enriching the flavours over time. The design of these teapots is often simple, emphasising functionality and the intimate relationship between the teapot and its user. Each Yixing teapot is unique, as it is supposed to reflect the personality of its creator.

Japanese matcha bowls

Japanese matcha bowls, or ‘chawan’, are another example of how ceramic design is influenced by tea. These bowls are traditionally wider and deeper, allowing the matcha to be whisked effectively. Their design varies from simple, uncluttered shapes to more complex, colourful patterns. They reflect the diversity of Japanese tea ceremony schools and traditions. Chawans, which are bowls specifically used for the Japanese tea ceremony, are designed to be held with both hands.

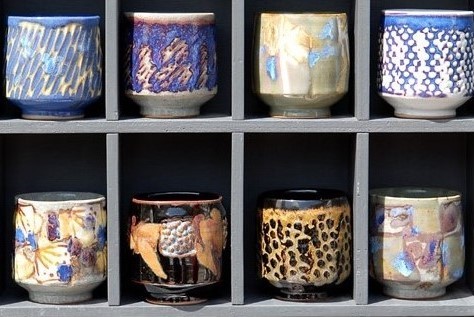

Yunomis

‘Yunomis’ are traditional Japanese tea bowls, typically made from stoneware or porcelain. They are part of the Japanese tea tradition, although they are less formal than chawans

Current trends in the world of tea

Teapots, bowls, cups, chawans, yunomis – the world of tea continues to inspire potters from every country and culture. The design of today’s teaware blends traditional and contemporary influences, with a growing emphasis on individuality and sustainability.

Minimalism and ecodesign

Clean, minimalist design, with its emphasis on simplicity and functionality, has become increasingly popular in recent years. Designs like this tend to favour natural colour palettes, expressing ecological concerns. There is also a tendency to fuse styles and techniques from different cultures. Elements of Japanese, Chinese and even Scandinavian design can be found in a single object, reflecting an increasingly interconnected world.

Today’s style

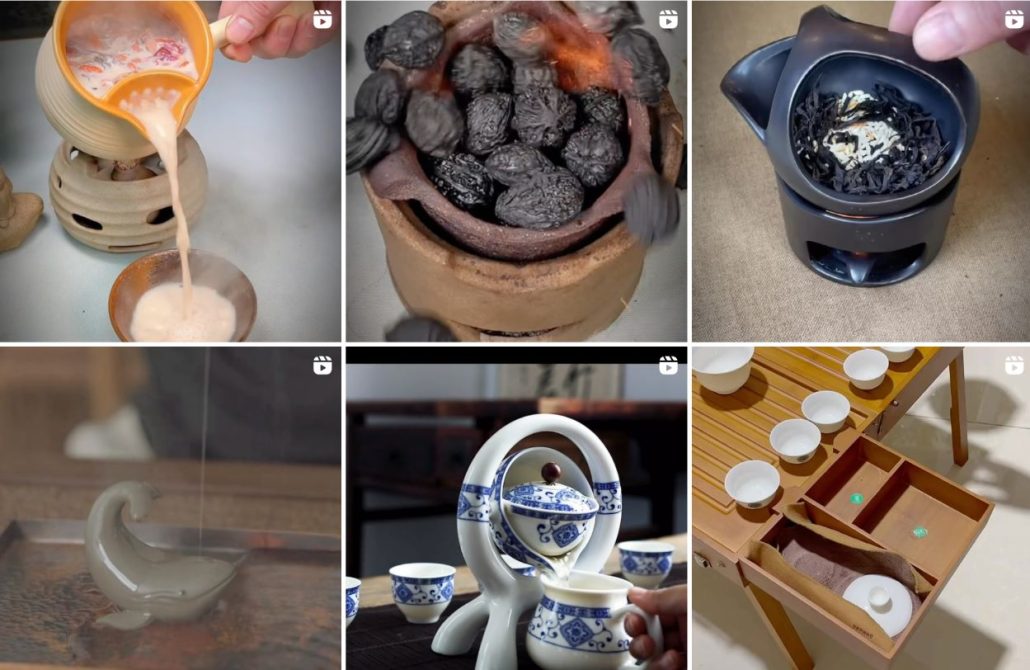

TangPin Tea

TangPin tea posts a video on tea preparation (including the creation of fragrances), and the use of containers. In particular, a range of easily made mini stoves are featured, easy to make, and keeping a nice cup of tea hot for a long time. The author often illustrates his points with a great deal of humour and even gags, which are a far cry from the contemplative atmosphere of tea ceremonies!

How to care for ceramic teaware

In order to preserve the beauty and functionality of ceramic teaware, we recommend washing by hand using lukewarm water and a mild detergent. Avoid abrasive sponges. After washing, dry immediately with a soft cloth to avoid water stains and mineral deposits. Store it in a safe place where there is no risk of it being knocked over or chipped. How teaware is used and cared for influences its patina and appearance over time.

Aesthetic impact of patina development

Yixing teapots: Yixing teapots are unglazed, and develop a patina after repeated use, as they absorb the tea’s aromas. This can enrich the flavour of future infusions. This can enrich the flavour of future infusions.

Porcelain and stoneware: glazed porcelain or stoneware items generally retain their original appearance for longer, especially with regular, careful maintenance.

Some items may change colour or stain over time, particularly if they are frequently used with highly pigmented teas. Fine cracks may appear on the glaze. This is often considered an aesthetic embellishment in tea culture, particularly in Asia.

Conclusion

Do inanimate objects have souls?

Exploring the world of tea immerses us in traditions and cultural expressions that originate in a quest for beauty, functionality and meaning. In each cup, in each teapot, there is a story, a bridge between the past and the present, between the sensory and the inner experience, acquired during the rituals that punctuate our existence.

Ceramics is in dialogue with tea, and this age-old partnership underlines a fundamental truth: the objects we make and use are not simply tools, they embody our values, our aspirations and our connection to the universe.. Ultimately, we are reminded that it is in the most ordinary actions that the most profound meditations on life, nature and art are often hidden.

Resource centre

animated by Matthieu Liévois,

potter-ceramist for over 40 years and founder of the Creamik School

Find all the courses

Keywords

Don’t miss any more news from the Créamik school!